Diabetes Insipidus: Causes, Symptoms, and Simple Treatment Guide

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is a condition that makes your body lose too much water through urine. It’s not related to blood sugar like diabetes mellitus. People with DI pee large amounts, drink a lot, and often wake at night to urinate. If you’re tracking symptoms, notice very dilute urine or sudden severe thirst—those are red flags.

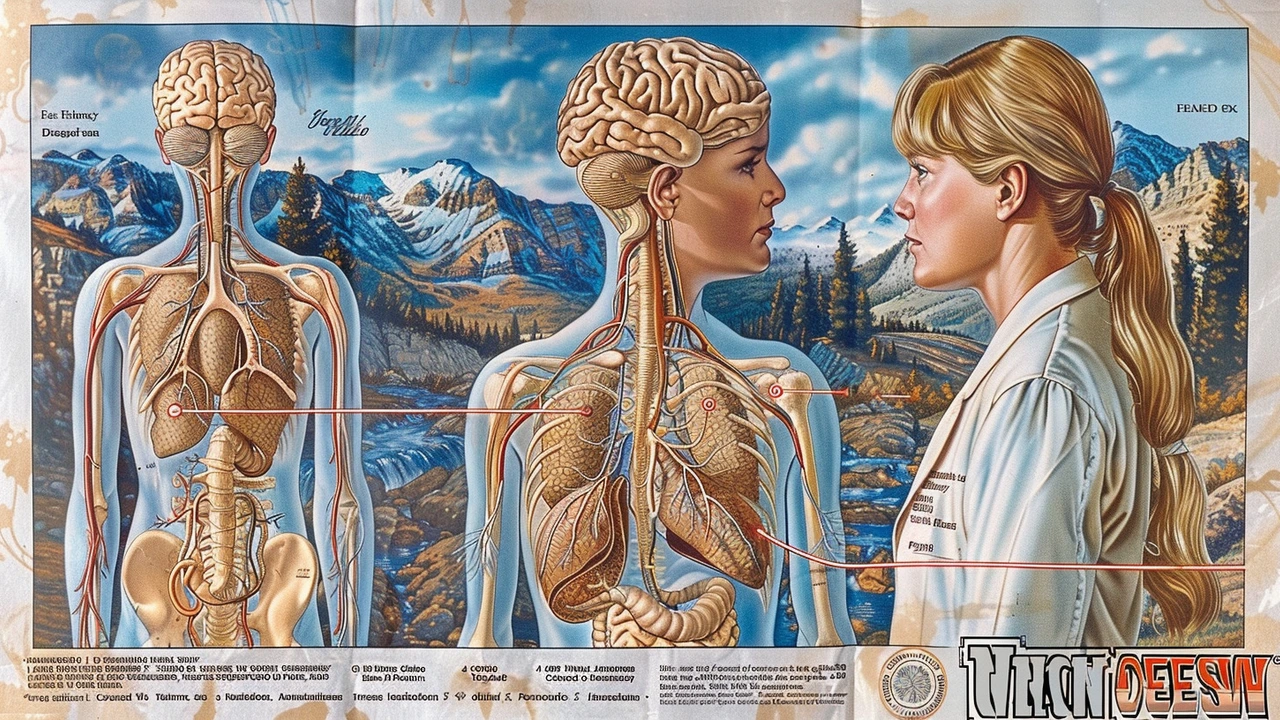

There are two main types. Central DI happens when the brain doesn’t release enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH), usually because of head injury, surgery, tumor, or rare autoimmune issues. Nephrogenic DI happens when the kidneys ignore ADH. That can come from genetic issues, lithium, some antibiotics, or chronic kidney disease.

How DI is diagnosed

Doctors look at your symptoms and run simple tests. A urine osmolality test checks how concentrated your urine is. Low urine osmolality with high blood osmolality suggests DI. Sometimes a water deprivation test is used under close supervision. Doctors may also give desmopressin (DDAVP) to see if urine concentration improves—this helps tell central from nephrogenic DI. Imaging like an MRI can check the pituitary gland if central DI is suspected.

Practical treatment tips

Treatment depends on the type. Central DI often responds well to desmopressin, a synthetic ADH you can take as a nasal spray or pill. Nephrogenic DI won’t respond to desmopressin; instead, doctors suggest low-salt diet, thiazide diuretics, or stopping the offending drug when possible. In both cases, staying hydrated is key—carry water, avoid heavy exercise without fluids, and watch for signs of dehydration such as dizziness, dry mouth, or low urine output after a period of forced fluid loss.

Keep a simple log for a few days: how often you pee, urine color, and how much you drink. That info helps your clinician. If you’re on medications like lithium, ask your doctor about monitoring kidney function and considering alternatives. For infants and older adults, DI can be risky because dehydration happens fast—seek care early.

Some practical steps you can take right away: measure fluid intake and urine output, avoid high-salt processed foods, and schedule blood and urine tests if symptoms persist. If you experience sudden confusion, very low urine output after vomiting or diarrhea, or fainting, get urgent medical attention.

Diabetes insipidus is manageable when diagnosed and treated. Learn the type you have, follow treatment advice, and stay on top of blood tests and follow-up visits. If you want to read related articles on medications, diagnosis methods, or safe online pharmacies, check the posts tagged with diabetes insipidus on this site.

Long-term care often includes regular blood tests to check sodium levels and kidney function. Women who are pregnant should tell their doctor, because pregnancy can change water balance and sometimes reveal DI. If you travel, plan for water access and carry prescriptions in original packaging. Wear a medical ID if you have severe DI so first responders know to check hydration and recent medications. Small planning steps cut risk and make daily life easier. Talk to your provider soon.

Understanding the Link Between Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus and Thyroid Disorders

This article explores the connection between central cranial diabetes insipidus and thyroid disorders. It delves into how these conditions interplay, affect the body, and what symptoms to watch for. Practical tips and interesting facts are provided to help those affected manage their health more effectively.

Health and WellnessLatest Posts

Tags

- online pharmacy

- medication safety

- generic drugs

- medication

- dietary supplement

- side effects

- online pharmacy UK

- drug interactions

- mental health

- impact

- online pharmacies

- statin side effects

- dosage

- adverse drug reactions

- generic vs brand

- pediatric antibiotics

- antibiotic side effects

- FDA drug safety

- skin health

- health