When a drug gets a safety alert, it’s not always clear whether the warning applies to just one medication-or to every drug in its class. This confusion can lead to unnecessary fear, missed treatments, or even dangerous prescribing mistakes. In 2018, the FDA issued a class-wide warning for all fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to risks of disabling tendon and nerve damage. Some doctors stopped prescribing them entirely. But later, they realized: for certain serious infections like complicated urinary tract infections, these drugs were still the best-or only-option. That’s the problem with unclear safety alerts. You need to know whether the risk is shared across the whole group, or locked to just one drug.

What’s the difference between class-wide and drug-specific alerts?

A class-wide safety alert means the risk comes from the shared chemical structure or biological mechanism of all drugs in that group. For example, all ACE inhibitors can cause angioedema (swelling under the skin) because they block the same enzyme. If one drug in the class triggers this reaction, it’s likely others will too. In 2023, the FDA updated labeling for all 12 testosterone products after studies showed they all raised blood pressure in some patients. That’s a class-wide signal.

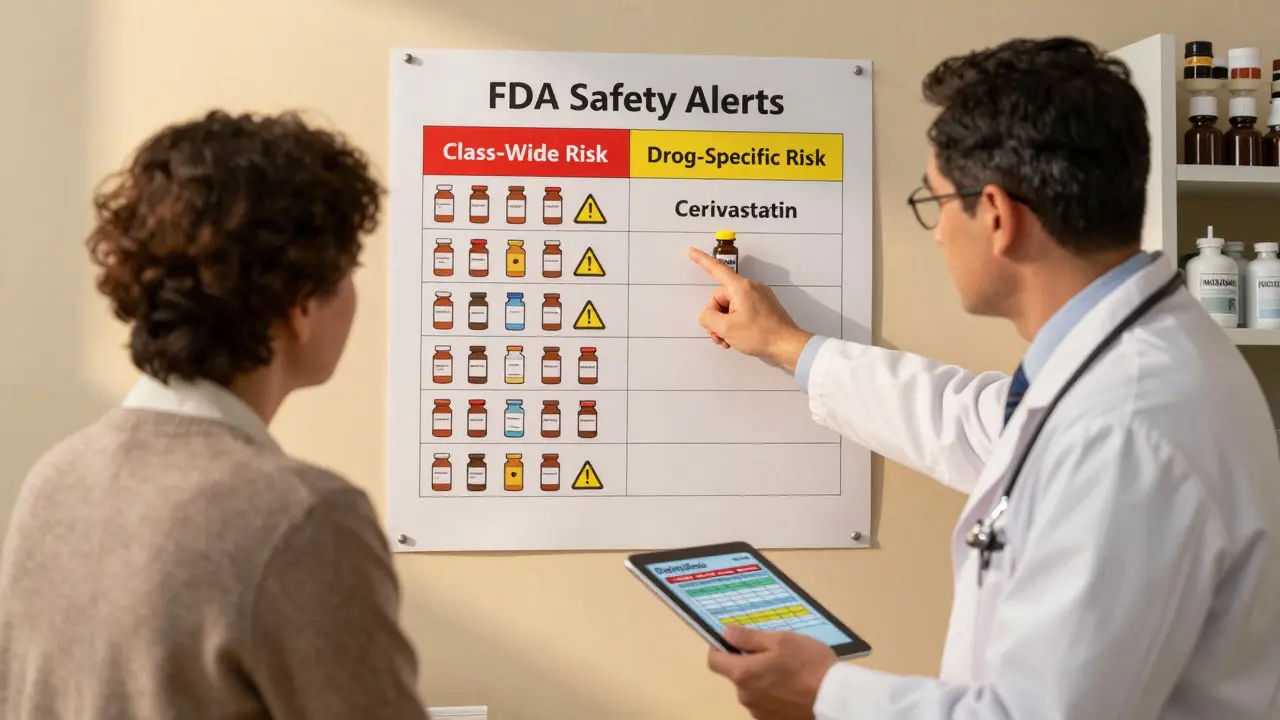

A drug-specific alert targets a single medication because of its unique chemistry. Cerivastatin (Baycol) was pulled from the market in 2001 after 52 cases of deadly muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis) were linked directly to it. Other statins-like atorvastatin or rosuvastatin-weren’t affected. Why? Because cerivastatin was metabolized differently and had a stronger effect on muscle cells. The risk wasn’t in the statin class-it was in that one molecule.

How does the FDA decide which type of alert to issue?

The FDA doesn’t guess. They use real data from millions of reports in the FAERS database (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System), which now holds over 22 million entries. They look for patterns. If three or more drugs in the same class show the same rare side effect-say, liver injury or heart rhythm changes-that’s a red flag for a class-wide issue.

They also check the strength of the signal. One report of a side effect? Not enough. But if a drug shows up 10 times more often than expected in reports compared to others in its class, that’s a statistical red flag. The Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR) must be above 2.0, and the Chi-squared value must be over 4.0 across multiple databases. That’s how they rule out random noise.

Then comes the science. Does the mechanism make sense? If all drugs in the class block the same receptor or are broken down by the same liver enzyme, it’s more likely the risk is shared. But if one drug is metabolized differently-say, by a different enzyme-or has a shorter half-life, it might escape the risk. That’s why not every statin carries the same muscle damage risk, even though they all lower cholesterol.

Why does this matter for patients and doctors?

Class-wide warnings change how entire groups of drugs are used. After the 2018 fluoroquinolone alert, prescriptions for the whole class dropped by 17%, according to IQVIA data. That sounds good-until you realize some patients lost access to a drug that was their only effective option. A 2022 survey of 1,200 U.S. physicians found 68% were confused about whether a warning applied to the whole class or just one drug. Primary care doctors were the most confused-73% reported uncertainty.

Drug-specific alerts are more precise. When valdecoxib (Bextra) was pulled in 2004 for heart attack risks, celecoxib (Celebrex) stayed on the market. That’s because celecoxib had a different chemical profile and didn’t carry the same level of risk. Prescribers could still treat arthritis safely. But here’s the catch: sometimes, evidence catches up. Rosiglitazone got a boxed warning in 2005 for heart risks, while pioglitazone didn’t. Later studies showed pioglitazone also carried some cardiovascular risk-but less. That inconsistency confused doctors for years.

What are the real-world consequences of getting it wrong?

When a warning is too broad, doctors stop prescribing safe drugs. When it’s too narrow, dangerous ones keep being used. In Pennsylvania, a 2023 report found that nearly 30% of high-alert medication errors involved insulin-because all insulin products look similar and carry similar risks. But the warning didn’t say which type was riskiest. Was it long-acting? Rapid-acting? The label didn’t clarify. That’s why pharmacists now spend 22% more time verifying prescriptions after class-wide alerts, compared to just 8% for drug-specific ones.

There’s also alert fatigue. When every drug in a class gets the same warning, doctors start ignoring them. That’s dangerous. In 2011, the FDA found that 33% of therapeutic classes with black box warnings had those warnings applied inconsistently. One drug got the warning, another didn’t-even though they were nearly identical. That created a false sense of safety. Patients on the "unwarned" drug assumed they were protected.

How can you tell the difference yourself?

You don’t need to be a regulator. Here’s how to check:

- Look at the exact wording of the alert. If it says "all drugs in this class" or "all X inhibitors," it’s class-wide. If it names one brand or generic, it’s drug-specific.

- Check DailyMed (from the National Library of Medicine). It color-codes warnings: red for class-wide, yellow for drug-specific.

- Search the FDA’s Drug Safety Communications archive. As of 2023, 18% were class-wide, 62% were drug-specific, and 20% were unclear.

- Look at the drug’s chemical name. Drugs ending in "-pril" (like lisinopril, enalapril) are all ACE inhibitors. If one has a warning, assume others might too-unless proven otherwise.

- Check if other drugs in the class are still on the market. If celecoxib is still sold after valdecoxib was pulled, the risk was likely drug-specific.

A quick rule of thumb: if the drug name has "cef" in it (like cefazolin, ceftriaxone), don’t assume all cephalosporins carry the same allergy risk. Only certain ones do. Same with sulfa drugs-not all drugs with "sulf" in the name are sulfa-based.

What tools help professionals make better calls?

Hospitals and pharmacies use AI tools now. IBM Watson Health’s Drug Safety Intelligence analyzes over 15 million FAERS reports and predicts class effects with 89% accuracy. The FDA’s own 2023 pilot program uses AI to scan molecular structures and predict which drugs might share risks before even a single adverse event is reported.

Training helps too. The American Medical Association found that after just 4-6 hours of continuing education on risk evaluation, doctors improved their ability to interpret alerts by 32%. That’s not a small win. It means fewer patients get caught in the crossfire of unclear warnings.

What’s changing in 2025?

The FDA launched a new warning taxonomy in January 2024. Now, every drug label must clearly say: "Class Risk" or "Agent-Specific Risk." No more guessing. This is a big step.

They’re also using real-world data from NEST-the National Evaluation System for health Technology-which pulls records from 100+ healthcare systems covering 100 million patients. That’s not just lab data. That’s what’s actually happening in clinics, pharmacies, and hospitals.

Still, challenges remain. Janet Woodcock, former FDA acting commissioner, pointed out that 72% of drug classes still lack enough post-market data to confidently say whether a risk is class-wide or not. Until we get better at tracking what happens after a drug is approved, we’ll keep making mistakes.

What should you do if you’re unsure?

If you’re a patient: Ask your pharmacist or doctor: "Is this warning for this drug only, or for all drugs like it?" Don’t assume. Write it down.

If you’re a provider: Don’t rely on memory. Always check DailyMed or the FDA’s website before prescribing. If a warning is unclear, consult a clinical pharmacist. They’re trained to spot these differences.

If you’re a caregiver: Keep a list of all medications you or your loved one takes. When a new alert comes out, cross-check each one. Don’t stop a drug without talking to a professional.

The goal isn’t to scare people away from medicine. It’s to use the right drug, for the right reason, with the right level of risk awareness. Class-wide alerts save lives. But so do precise, drug-specific ones. The difference between them can be the difference between healing and harm.

How do I know if a safety alert applies to all drugs in a class or just one?

Check the official FDA Drug Safety Communication or DailyMed. Look for phrases like "all drugs in this class" or "all ACE inhibitors"-those mean class-wide. If only one brand or generic name is mentioned, it’s drug-specific. Avoid assuming based on drug names alone-like "cef" or "sulf"-because not all drugs with similar names share risks.

Can a drug-specific warning later become class-wide?

Yes. Rosiglitazone got a boxed warning for heart risks in 2005, while pioglitazone didn’t. Later, data showed pioglitazone also carried some cardiovascular risk-just lower. This led to confusion and updated labeling. Class-wide warnings often emerge after more real-world data accumulates, especially when multiple drugs show similar patterns over time.

Why do some drugs in the same class have different warnings?

Because drugs in the same class can have different chemical structures, metabolism pathways, or dosing. For example, cerivastatin was withdrawn due to rhabdomyolysis, but other statins like atorvastatin weren’t, because they’re processed differently by the liver. The FDA evaluates each drug’s unique profile-even within a class-before issuing warnings.

Are class-wide warnings always accurate?

Not always. Incomplete data, limited studies, or early signals can lead to overly broad warnings. The FDA admits that 72% of drug classes lack enough post-market data to confirm risk scope. That’s why some class-wide alerts are later revised. Always check for updates and consult current guidelines.

What should I do if my doctor stops prescribing a drug because of a safety alert?

Ask: "Is this warning for this drug only, or for all drugs like it?" If it’s class-wide, ask if there’s a safer alternative within the same class. If it’s drug-specific, ask if another drug in the class is still safe to use. Never stop medication without discussing alternatives-some drugs may still be the best option for your condition.

Pawan Chaudhary

16 December 2025This is such a clear breakdown-I wish more doctors had read this before pulling my meds last year. Glad someone finally explained the difference between class-wide and drug-specific alerts in plain English.

Philippa Skiadopoulou

18 December 2025The FDA’s new taxonomy requiring explicit classification as 'Class Risk' or 'Agent-Specific Risk' is a necessary and long-overdue reform. Clarity in regulatory communication is not optional-it is a matter of clinical safety and legal accountability.

Marie Mee

20 December 2025They're lying about the data. The FDA hides the real side effects so Big Pharma can keep selling. You think they care if you get rhabdomyolysis? Nah. They just want your insurance to pay

Linda Caldwell

20 December 2025Stop panicking and start asking questions. If your doctor freezes up when a warning drops, that's not the drug's fault-it's the system's. Push for DailyMed checks. Keep a med list. You're your own best advocate. You got this.

Joe Bartlett

20 December 2025UK doctors don't get confused like this. We know our meds. Americans overthink everything.

Naomi Lopez

22 December 2025It's fascinating how the FDA’s reliance on FAERS data-flawed, passive, and unstandardized-still governs clinical practice. The fact that we're using 1970s pharmacovigilance models in 2025 is less a policy failure and more a cultural surrender to bureaucratic inertia.

Salome Perez

24 December 2025As someone raised in a household where medication was treated with reverence-not fear-I’ve learned that understanding the nuance between class-wide and drug-specific alerts isn’t just medical literacy, it’s cultural wisdom. In my grandmother’s village in Oaxaca, they knew which herbs to avoid in pregnancy by observing generations. We’ve lost that intuition. Now we need AI and color-coded labels to do what instinct once did. Let’s not romanticize the data. Let’s restore the relationship between patient and medicine.

Kent Peterson

25 December 2025Wait-so you're telling me that the FDA, the same agency that approved Vioxx, then pulled it, then approved another drug with the same chemical backbone, and now they're 'fixing' this with a 'taxonomy'? This isn't reform-it's rebranding. You think a label change fixes 30 years of systemic incompetence? You're delusional. And don't even get me started on IBM Watson's '89% accuracy'-that's like saying a broken compass is 'mostly right'.

Jonathan Morris

27 December 2025Let’s be real: the entire class-wide vs. drug-specific framework is a distraction. The real issue? The FDA doesn’t have the resources to test every metabolite pathway. So they use statistical noise as gospel. And then they blame doctors for not knowing the difference. Meanwhile, the same 5 corporations control 90% of the drugs in every class-and they fund the very studies that 'prove' safety. This isn’t science. It’s corporate theater with a side of regulatory theater.